Everyone loves a good paradox.

Here’s one we’ve all heard before:

Jason goes on a date with a girl. He and the girl, we’ll call her Amy, sync almost immediately. They drink coffee and talk about everything from life and ideal travel destinations to their favorite breakfast foods. A few days later, though, Amy shows no interest in going for a second date. Jason goes crazy, then, because that’s what you do. “I don’t get it,” he says. “We hit it off right away. She was all over me!”

He ends up infatuated, brainstorming reasons to message her on Facebook, and spends a month lamenting her as “the one that got away.” Then one day Amy calls. She wants to go for coffee.

“So why didn’t you go?” I say.

“I don’t know,” he shrugs. “I just wasn't feeling it.”

***

While Jason’s predicament embodies the ridiculous nature of dating today, it’s not an entirely modern theme. Shakespeare wrote about it in 17th Century, and Tolstoy in the context of 19th Century Russian Society: the push and pull of the id and ego, the illusion of movement, the partnered dance without touching.

Tolstoy wrote about another paradox: how society is necessary for the survival of the individual, and yet it annihilates the individuality of its members. How in the words of Polonius from Hamlet, “to thine own self be true” means that—in the face of society’s corruption—in order to maintain any sense of personal authenticity we must first succumb to madness. Joseph Heller called this idea Catch 22; Lionel Trilling, "the authentic unconscious.”

There are other paradoxes. Like how happiness is measured by sadness, and how we can be constantly surrounded by people—living in the most densely populated cities on earth—and yet never have felt more alone.

Traveling has taught me how to make quick friends. Spend ten nights in ten different cities, a new hostel each time, and you’ll learn how to talk with anyone about anything. “24-hr Companions,” that’s what I titled them in my blog post from The Flight of a Boomerang.

One of these companions I met in a Seattle hostel. His name was Neals and he was from Denmark. His plan had been to come to America and buy a used car, roadtrip around the countryside, and then sell the car before flying home. Eventually, he learned that he couldn’t buy a car because he wasn’t a legal resident, so he deferred to riding Greyhound buses from city to city, skipping all of the wild parts between and surfing concrete.

We joined up with a Brazilian and the three of us hit the town like a scene from Jack Kerouac’s On the Road. Neals and I spent the bulk of our night trying to woo a pair of married sisters from Texas (because that’s what you do), then we made plans to cross the open North together: to skim Yellowstone and Glacier National and Mount Rushmore, camping along the way and drinking in the sights. I left him in the hostel lobby chatting up a Canadian bird and when I woke up in the morning he was gone.

“Caught a bus to Portland,” said the girl. “Left before dawn.”

Because that’s what you do.

Our world is full of paradoxes. Here’s one that sums up the rest:

Life walks hand in hand with death.

***

Wrapping your head around a paradox is a lot like standing at a tram stop in Budapest, watching the girl you just kissed disappear behind sliding glass doors and knowing that you’ll never see her again.

Her name was Karlee and we met because one night Jason, my host, locked me out of his flat to chase up an ex-girlfriend. A few nights later I took her out for dinner. She was from Austria but had been living in Budapest for over two years, attending the medical school there. She had hair shorter than mine and green eyes that paled in the light.

We ended the night on top of a hill that overlooked the east side of town. City lights shimmered off of the Danube and a spring draft held Karlee tight in my arms. We didn’t end the night in each other's bed making daft promises about the future, but—sitting there before the lights on Chain Bridge—I remember feeling her fingers lace with mine and realizing that I hadn’t “held hands” with anybody in almost a year.

We returned from Budapest and Jason decided to go on a second date with Amy. When he came back, the look of disillusionment on his face was enough to match Tolstoy’s Anna Karenina.

“It was alright,” he said.

He stopped looking for excuses to message Amy after that, and I never heard from Karlee again. But here’s a paradox that sticks: loneliness pushes us to interact. It forces us to connect with people we wouldn’t have met otherwise. And I’m not talking about one-night stands or our tendency to get black-out drunk before gathering up the courage just to speak with someone. What I mean is the phenomenon of the Human Connection; the transience of true beauty; how paths can cross in the dark, and even though they don’t lock or change course they might still bend in the night—joining, if just for a moment—only to spring back into place all the more alive with movement.

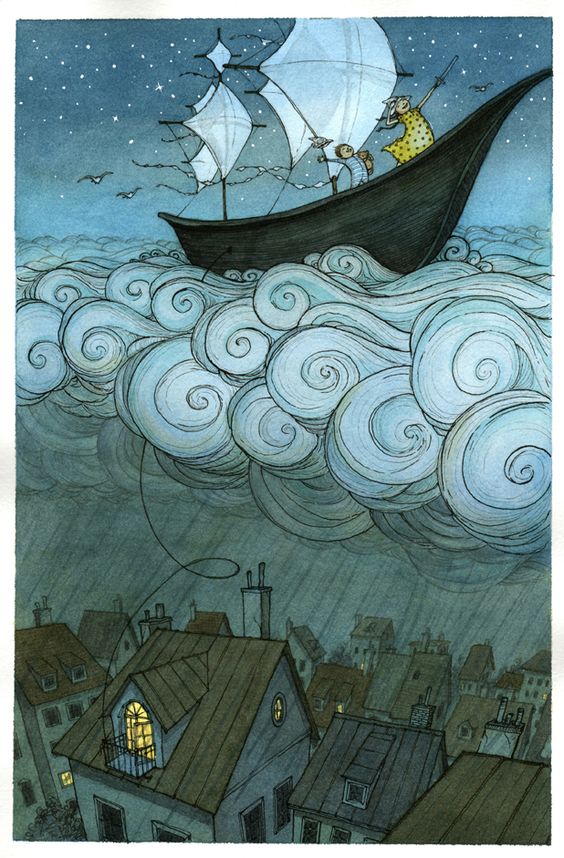

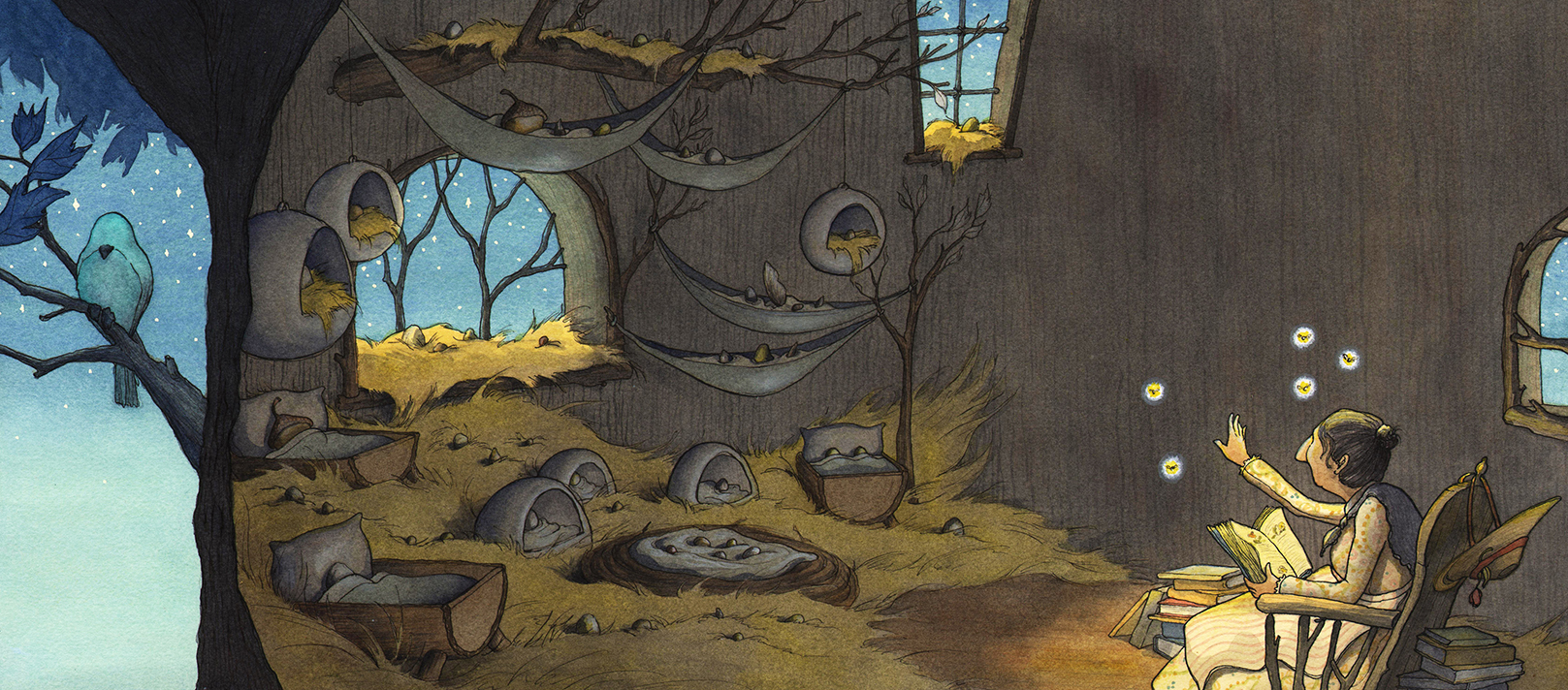

Illustrations by author-illustrator Eliza Wheeler